Embark on a journey through the history of one of the oldest universities in Germany. Works of European painting, sculpture, graphic art and handicrafts from the Middle Ages to the present provide an insight into the eventful 600-year history of a university steeped in tradition. The University presents the highlights of its art collection inside the former “Royal Palace”, now the Rectorate building.

600 years of art at Leipzig University

Visitors can marvel at works of art from the Dominican monastery, founded in the thirteenth century, which was located on the site of today’s Augustusplatz campus. These include the mysterious sculpture of the knight Dietrich of Wettin and a legendary painted panel known as the Böhmische Tafel. Valuable insignia such as sceptres, seals and national emblems bear witness to the University’s foundation in 1409 and its constitution. Portraits of Martin Luther and Philipp Melanchthon, as well as paintings by Lucas Cranach the Elder, his son Lucas Cranach the Younger and their contemporaries illustrate the close association between the University and the Reformers. Portraits of important scholars and artists highlight how these individuals shaped academia and the city of Leipzig. The collection of portraits painted by Anton Graff for the Leipzig publisher Philipp Erasmus Reich shows poets, thinkers, artists and statesmen of the Enlightenment. Views of University buildings and a model of the city show how the University grew.

The Sceptres of Leipzig University

Dominican monastery and early years

Historically, the University of Leipzig (“Alma mater Lipsiensis”) is an offshoot of the Charles University in Prague. After masters and students of German origin left Prague because of what they perceived to be political oppression, a new university was founded in Leipzig in 1409 with the support of the Margraves of Meißen and the permission of the Pope. Frederick IV, also known as the “Quarrelsome”, and William II granted them property and the right to self-administration. This special status is symbolised in the art collection by insignia such as the pair of sceptres (1476) and the rector’s small seal (1592). Following the example of Prague, the new university was structured on the principle of four faculties and four “nations”: Meißen, Saxony, Bavaria and Poland. These are reflected in four painted 17th-century shields that originally adorned the University Hall (“Nationenstube”).

Today, many aspects of the University’s history can only be found in its art collection. Virtually no trace remains of the original buildings, as they were continually rebuilt in more modern styles and on a grander scale. The oldest college buildings were located in the south-western part of the medieval city, between the Schlossgasse and Petersstraße, where the city council had allocated buildings for use by graduates even before the University was officially founded. These buildings, later enlarged to form the “Kleines Fürstenkolleg”, housed the Faculty of Law from 1508 onwards (first called the “Petrinum” and since 1881 the “Juridicum”). The main campus, however, was located on the eastern edge of the medieval city, in the “Latin Quarter” between the city wall (now the Goethestraße) and the Ritterstraße. The complex of buildings became the seat of the Faculty of Arts (artes liberales). The new campus included the “Großes Fürstenkolleg” complete with dormitories (“Bursen”), a large heated lecture hall (“Vaporarium”), which also served as an assembly hall (“Nationenstube”), and various colleges, such as the “Kleines Colleg” and the “Rotes Colleg”.

Reformation and Baroque

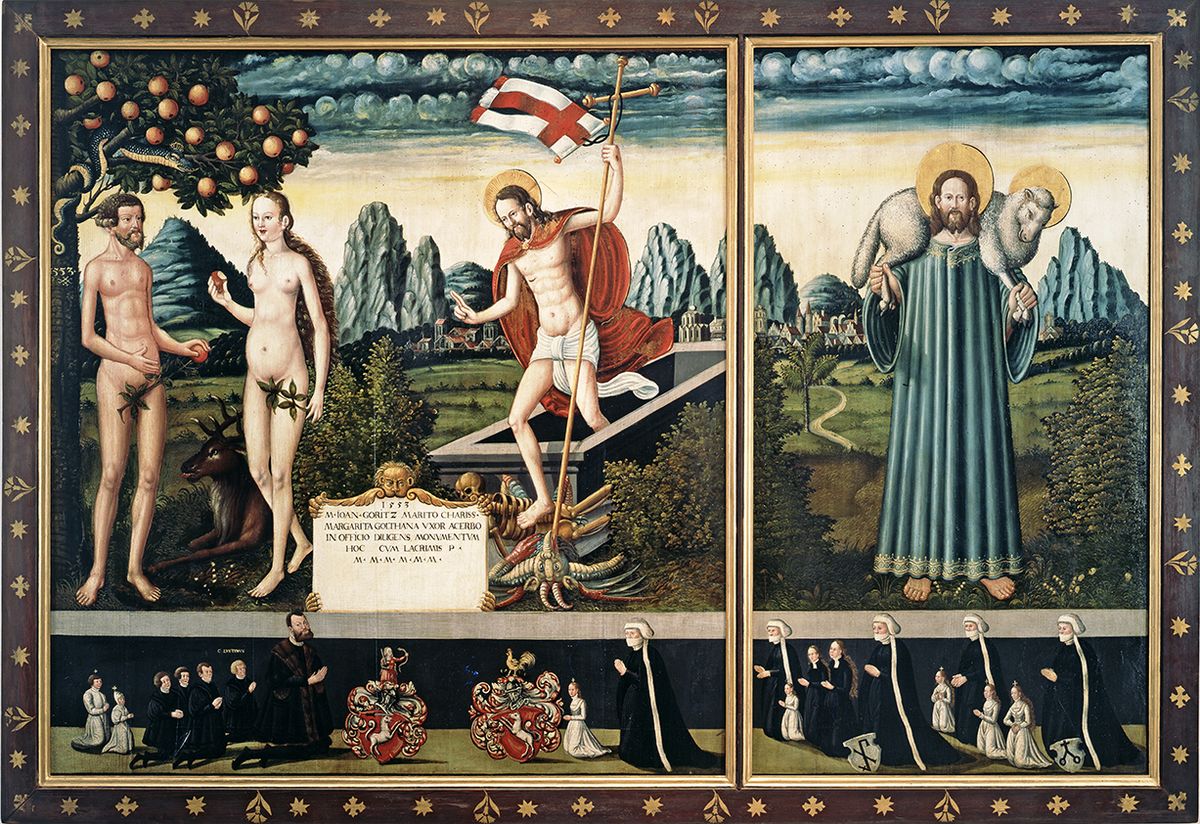

The introduction of the Reformation in 1539 resulted in the donation of even larger premises. In 1543 Grand Duke Moritz bequeathed the newly secularised Dominican monastery of St. Paul, to the south of Grimmaische Straße, now the area between Grimmaische Straße, Universitätsstraße, Augustusplatz and the Moritzbastei. Numerous important medieval works of art in the collection testify to the wealth and culture of the former monastery, such as the life-size wooden sculpture of St. Thomas Aquinas teaching and a double-sided painted altarpiece, both completed around 1400. The late 15th-century high altar of the Paulinerkirche is exhibited in the Thomaskirche as a loan from the University to the church. The close ties between the University and the Reformation movement are documented by numerous portraits of Luther and Melanchthon, paintings with Protestant iconography such as Christ and the Children from the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, and painted epitaphs such as the one for Johann Goritz dating from 1553.

For the growing university, the acquisition of the monastery library represented a significant improvement in teaching conditions. At the same time, the new premises provided the much-needed space for lecture halls, refectories and dormitories. Founded in 1240, the Paulinerkirche was rebuilt according to Protestant ideas and consecrated as the university church in 1545. Its spacious interior was used not only for disputations and graduation ceremonies, but also as a burial place for the university elite, a practice that continued until the late 18th century. Over the centuries, this tradiation produced an important ensemble of epitaphs, which continued to inspire pride and confidence in later generations. In 1968, however, the communist rulers decided to demolish the church to make room for socialist ‘urban development’. Before the church was literally blown up with explosives, many works of art were miraculously saved. The current exhibition presents a selection that has been restored, but many pieces still await restoration for display in the new university hall/church on its original site.

The University’s post-Reformation history is also reflected in numerous portraits of professors. The “Ordinariengalerie” of the Faculty of Law [6] includes portraits of department heads from the 16th to the 19th centuries and is the only systematically planned gallery of professors at the University. From the mid-17th century, there was an increase in donations of portraits from private benefactors, many of which were gifts to the University Library. Of particular interest to art historians is the Gallery of Friendship from the late 18th century. The collection consists of portraits commissioned by the Leipzig publisher and bookseller Phillipp Erasmus Reich. Reich was associated with many famous writers, artists and philosophers of the Enlightenment, including Moses Mendelsohn, Lessing and Sulzer from Leipzig and Lavater from Zurich. Predominantly painted by Anton Graff, the pictures include several university professors, such as C. F. Gellert and J. A. Ernesti.

The so-called “deposition instruments” are of special importance in the history of student life at the University, as they are relics of an ancient initiation rite for new students. The term derives from the Latin depositio cornu, which means “removal of the horns”. An incoming student was required to don a hat with horns, a symbol of his uncouth, Dionysian nature, the forcible removal of which symbolised his passage into civilised society. The student was also “groomed” with oversized combs, razors, axes and planes. After repeated cases of injury and even death, the initiation was finally abolished in 1719. Similar rites were common at many universities throughout Europe, but the necessary ‘tools’ have only survived at Leipzig.

State university (18th and 19th centuries)

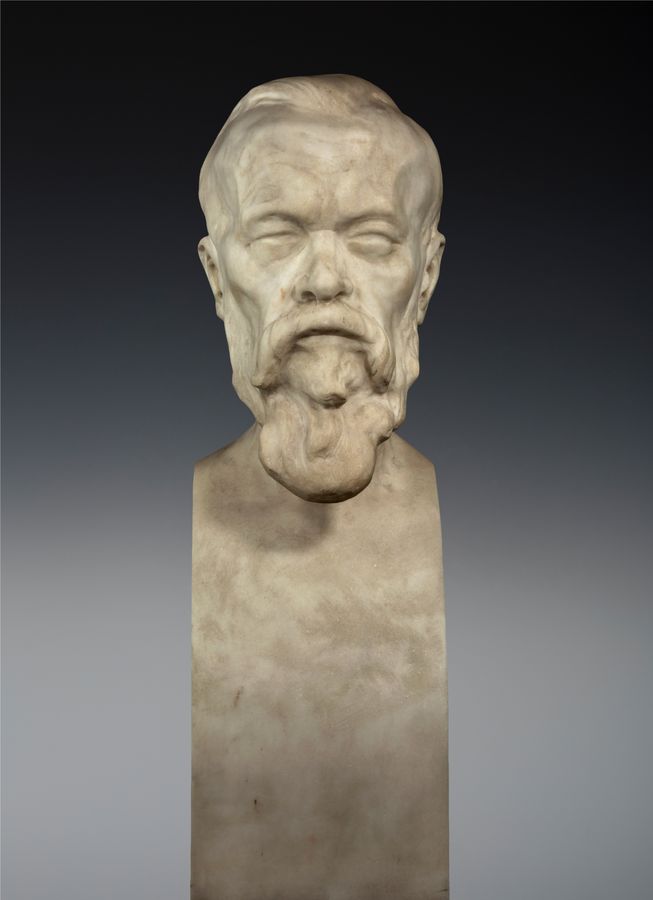

From 1830 Leipzig University began to develop into a modern state university. The new beginning was accompanied by an ambitious building programme, which is documented in the collection by several cityscapes on paper. Between 1830 and 1836 the first main building, the Augusteum, was erected on Augustusplatz based on designs by A. Geutebrück. Its sculptural decoration by E. Rietschel (1801−1864), such as the tympanon on the façade and the cycle of twelve reliefs for the university hall, was largely destroyed in 1944, but an important architectural fragment in the form of the monumental entrance gate, known as the “Schinkelportal”, has survived. The mid-19th century also saw the construction of new institute buildings, both on the grounds of the monastery and in the “Academic Quarter” on the city’s south-eastern periphery, which are well documented in etchings and lithographs. The years around 1900 saw the start of yet another building campaign. Between 1892 and 1898, the original Augusteum by Geutebrück was re-modelled by A. Roßbach in a historicist style, following in the classical footsteps of his predecessor. In addition to a new façade facing Augustusplatz, the building was given an impressive foyer and a much larger university hall. However, much of the interior of the Augusteum was destroyed in the Second World War. The monumental mural painting The Flourishing of Greece (1907−1909) in the auditorium by the Leipzig Symbolist painter and sculptor Max Klinger was lost. In the years around 1900, the University had a particularly close relationship with Klinger and commissioned several works from him. In the exhibition, Klinger’s marble bust (1908) of the psychologist and former professor Wilhelm Wundt testifies to this special relationship. Some of the interior furnishings of the Augusteum have survived, such as the portrait bust of the art historian Anton Springer, signed by Carl Seffner and dated 1892. The oil painting by Vogel von Vogelstein (1841) of Gottfried Hermann, professor of classical philology, is just one example of a representative collection of painted portraits from the 19th century.

How to find us

The art collection is located on the ground floor of the Rectorate building on the corner of Goethestraße and (Kleine) Ritterstraße, one of the University’s oldest properties. The current building was erected in 1860/61 by the university architect Albert Geutebrück (1801–1868) as a “royal palace” for visits by the King of Saxony to Leipzig, and the interior was remodelled in the Rococo style in 1895/96 by Arwed Rossbach (1844–1902).