In addition to the ongoing management and care of the University's art collection, we also oversee a number of temporary projects. The construction project on the Augustusplatz campus was the focus of our work from 2002 to 2017. Projects included the relocation of historic artworks to the new buildings of the Neues Augusteum and the Paulinum. Many works of art were returned to their original location after decades in storage. We are still in the process of adding works of art to the Augustusplatz campus.

Current projects

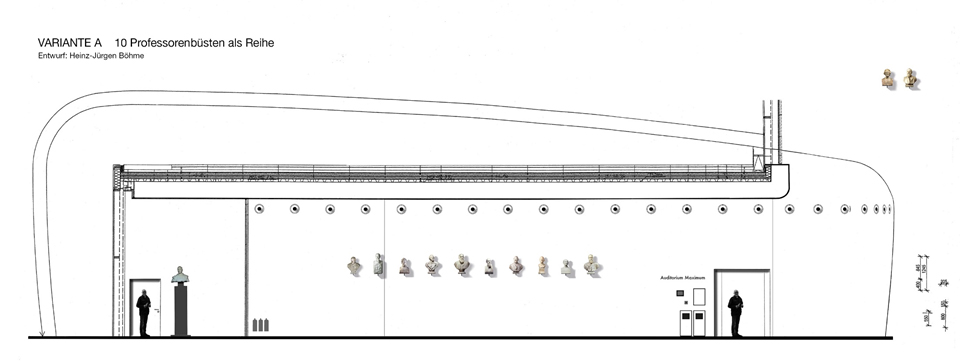

Installation of a ‘bust grove’ in the Neues Augusteum

The original design of the first Augusteum, built in 1831-36, included a number of busts in the interior. The intention was to honour scholars and statesmen who had rendered outstanding services to the University. Gradually, 12 busts were installed in the assembly hall. The reference to the Saxon royal house, already present in the naming of the building and the seated figure of Friedrich August I, was extended by the busts of the Saxon kings Anton and Friedrich August II and the Saxon princes Maximilian and Johann, created by Ernst Rietschel. In the course of the Gründerzeit reconstruction by Arwed Rossbach in 1891–97, parts of the sculptural furnishings of the assembly hall were moved to the newly built Wandelhalle and supplemented by further contemporary busts.

Carl Seffner created most of the portrait busts in plaster or white Tyrolean marble. His masterpiece is the bust of the art historian Anton Springer from 1892, which brought him numerous commissions. Other sculptors who were commissioned were Ernst Rietschel, Adolf von Hildebrand, Johannes Schilling and Robert Eduard Henze. During the Second World War, many of the busts were damaged or lost in the firestorm of 4 December 1943. The heavy marble busts fell from their plinths. The material destruction can be seen, for example, in the bust of the mathematician Moritz Wilhelm Drobisch, which was recovered from the rubble of the assembly hall. The bust of the philologist Friedrich Ritschl also shows the extent of the devastation, with its broken nose and drops of melted metal.

A new installation of selected busts will be realised in the Neues Augusteum. They will be placed in the foyer in front of the Auditorium maximum.

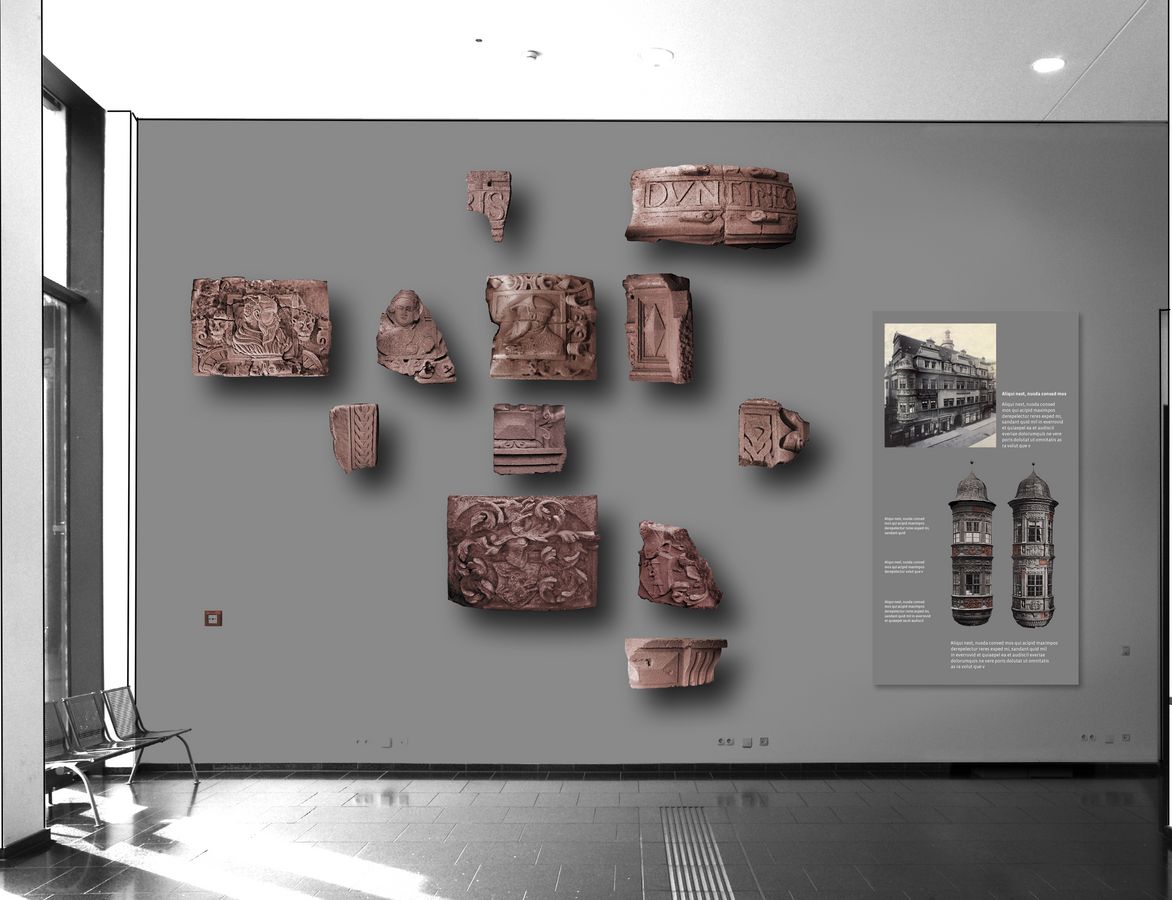

Restoration and reinstallation of Renaissance fragments

The Fürstenhaus (Prince’s House) on the corner of Grimmaische Straße and Universitätsstraße was considered one of the most important Renaissance buildings in Central Germany. The most striking decoration of the house were the two round oriels made of Rochlitz porphyry at the northeast and northwest corners. They showed coats of arms and profile portraits framed by the finest Renaissance ornamentation.

Subsequently, it was mostly rented out and served as a department store in the first half of the 20th century. During the night of bombing on 4 December 1943, the building was destroyed to its foundations. However, post-war photographs and prints show the staircase tower protruding from the rubble. After the fragments of the two oriels had been stored in the Moritzbastei for several decades, the Leipzig city administration had a replica made of Rochlitz porphyry by the Dresden stonemason Julius Hempel in the 1980s. This was mounted on the new building opposite, built in the 1980s, at Grimmaische Straße 17. Only recently has it been discovered that the original fragments remained in the courtyard of the Dresden stonemasonry firm, from where they returned to Leipzig University in 2011.

The installation on the site of the former Renaissance building will be accompanied by a detailed explanation, an art history seminar, an exhibition in the gallery of the Neues Augusteum and a publication. On the basis of the funding now secured, the first step will be to restore the fragments, and the second step will be to install them in the stairwell of the University’s Faculty of Economics and Management Science (corner of Grimmaische Straße and Universitätsstraße). The fragments will thus return to the former site of the Fürstenhaus after some 80 years. In view of the very partial preservation of the two oriels, it is planned to present the fragments in the form of a lapidarium, which will demonstrate their high sculptural quality. The project is expected to take two to three years to complete.

New installation of two steles by the sculptor Friedemann Lenk

The Saxon sculptor Friedemann Lenk (1929−2021) had a decisive influence on the visual arts in the GDR. His Technoskulpturen are representative of the artist’s idiosyncratic work. The two steles recall his deep preoccupation with geometry and technology. Their formal language stands for technical movements that find their harmony in the artistic deformation of the natural material wood. However, this seemingly technical modification is an illusion and on closer inspection reveals the work of a sculptor.

The three-metre-high stelae were commissioned by Karl Marx University in July 1976 and officially handed over a year later. They were then installed in the foyer on the ground floor of the lecture hall building. The free-standing sculptures did not have a load-bearing function, but rather served as structuring spatial signs for the design of large rooms. Due to the increased use of the foyer by the growing number of students, the steles were later moved under the staircase. In 2004 the sculptures were finally removed and placed in storage.

There are now plans to reinstall the Technoskulpturen. They will regain their original representative function as a spatial element.

Return of the gravestone of Duchess Elisabeth of Saxony to the University

Elisabeth of Bavaria (1443–1484), a Wittelsbach duchess, was married to the Wettin elector Ernst of Saxony on 19 November 1460 in the Church of St Thomas in Leipzig. Since the late Middle Ages, the city had been one of the Wettin family’s changing permanent residences. When she died in Leipzig on 5 March 1484, her body was transferred from the sovereign’s Pleißenburg castle to St Nicholas’s Church for the Requiem Mass and the final civic homage. She was then buried in the Dominican Church of St Paul.

The bronze plate, made from six sections joined together by rivets, was probably made by a Central German foundryman in 1484/85. The object measures 202 x 114 cm and is framed in oak. The slab originally covered a grave in the choir of the church, at the end of the central aisle facing the altar. The tomb was covered with a red slab of Rochlitz porphyry, which distinguished it from the other tombs. The bronze plate was placed on the stone.

The contents of the burial chamber were probably moved during the Schmalkaldic War, when the choir of St Paul’s Church, which overlooked the city wall, fell victim to defensive measures. In the 19th century, the tomb slab was separated from the tomb and repositioned on the wall during the reconstruction of the church.

The slab shows the Electress in religious dress with a veil, her eyes closed and a rosary between her praying hands. The coat of arms of the Saxon-Bavarian alliance to the left of the deceased and the inscription, interrupted in the corners by medallions with the symbols of the Evangelists, refer to her secular rank as Duchess of Saxony, Landgravine of Thuringia and Margravine of Meissen.

The slab is currently on loan to the Thomaskirche in Leipzig; a possible return to the Paulinum is still under discussion.

Project archive

Hanging of two additional epitaphs

On the wall behind the Pauline altar, two additional memorial tablets were mounted, which had previously been stored in the art depot of Leipzig University. These are the epitaphs for Joachim Friedrich Zoege von Manteuffel (1610−1642) and Conrad Kleinhempel (1607−1662), which date from the time of the Thirty Years’ War and the decades immediately after it respectively. To make room for the new objects, the epitaphs of Anna Regina Welsch and Christoph Zobel, which were already mounted on the wall, were moved slightly downwards.

During the Thirty Years’ War, the University Church of St. Paul served as a burial place for the Swedish military. Zoege von Manteuffel, who served as a lieutenant colonel, fell in 1642 near Leipzig and was subsequently buried in the church. The present copy of the memorial is the only evidence of this burial. The wooden inscription panel replaces a presumably textile original, which was ‘renewed’ in its present form in 1740. The grooved frame attached to the panel is original. The joints between the individual boards of the panel had opened up, and there was also evidence of earlier woodworm infestation. Extensive restoration work has closed the cracks and made the work fit for display. The memorial for Conrad Kleinhempel, a civil servant who worked as a tax collector and raft inspector for the city of Leipzig, is a blackened cast bronze panel with gilded letters. The epitaph was previously only on display as part of an exhibition in the gallery of the Neues Augusteum and has now found its place in the chancel of the Paulinum.

In addition to restoring the works of art, the epitaph project also called on the curatorial expertise of Professor Rudolf Hiller von Gaertringen, who developed a concept for the hanging of the epitaphs in dialogue with the art commission convened by the rectorate. The prominent installation of the epitaphs was carried out on hanging surfaces between the pillars of the altar room in the Paulinum. After the successful installation of the ‘floating walls’, a total of 21 large epitaphs were installed on them between 2014 and 2017. The largest memorials are five to six metres high and three to four metres wide. Given the often irreversible structural damage to the artworks, the reinstallation of the individual assemblies was a major challenge. For this reason, the installation was carried out using an innovative hanging technique involving invisible, rear-ventilated stainless steel scaffolding. For example, the monumental stone epitaphs, which consist of a large number of elements, often weigh well over a tonne. Smaller epitaphs were placed in the chancel to complement them. After fifteen years of intensive work on the epitaph project, the finish line was reached in 2017.

The University included the reinstallation of the epitaphs as a condition in the tender for the new Augustusplatz building project. Works of art that had lost their spatial context due to the demolition of university buildings under socialism were to be returned to their original locations, provided that the new architectural framework allowed for this. A decision was taken by the art commission to hang the epitaphs in a way that integrates the memorials into a cross-campus art concept from the Middle Ages to the present day.